When we speak of religions today, they are often described like products in a supermarket: packages of beliefs, rules of conduct, symbols, and rituals, which are offered by specific brands. These brands advertise their own particular product range: reincarnation in the package of one religion, a heaven in that of the other; prayer in the package of one religion, meditation in that of the other; priests in the package of one religion, rabbis in that of the other. Some brands additionally offer multiple variants of their merchandise, such as a Sunni version and a Shia version, or a Japanese Zen edition and a Thai Theravada edition. However, no elements are exchanged between the brands, let alone trade secrets. After all, each brand wants to outcompete the others, and obtain a monopoly in the religious market.

Such a view of religion is problematic. Most religions do not have a straightforward “product”, they are not “managed” like distinct companies, and their “merchandise” is constantly exchanged. In my book Religion: Reality Behind the Myths I give plenty of examples: witchcraft in Christianity, Jewish Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims performing rituals together, old shamanistic practices that still live on in mainstream traditions, religious atheists in various denominations, and so on. When we keep our eyes open, we can easily discover plenty of phenomena that shake the dominant ideas about religion.

If we would like to achieve a better understanding of religion, it seems apt to forgo the corporate metaphors and make a comparison to language. Such a comparison can clarify more easily why the boundaries of different religions are so porous and fluid. For example, we know that languages can mix in many ways because of loan words (like the many English words in contemporary Hindi), because a complete “intermediate language” arose (like Creole), or because some people deliberately created a mixed language (like Esperanto). Similarly, religions can sometimes adopt specific rituals (like the use of prayer beads in different traditions), a complete “intermediate religion” can sometimes arise (like Sikhism, which combined elements from both Hinduism and Islam), or some people might consciously create a syncretic religion (like the Din-i-Ilahi of the Mughal Emperor Akbar, who tried to unify ideas from the several religions in his region and era).

We also have little trouble with the concept of multilingualism. Not only do some people grow up in a family where several languages are spoken, all of us can also choose to learn an extra language. Likewise, it should not come as a surprise that the contemporary academic term “multiple religious belonging” is, in fact, applicable to a large segment of the world’s population for many centuries. Some people grow up in a context where various traditions surround them on a daily basis and all of us can choose to delve into a tradition that we were not raised in. Of course, in the case of languages, our native language usually remains the one in which we are most proficient, and which comes to us most intuitively. Yet here again, we can easily find a similarity, for even when people convert, concepts from their “mother religion” often still influence their thinking.

Another parallel can be drawn with dialects. After all, a patchwork of dialects ensures great internal diversity within every language. The differences within dialects can sometimes be so profound that those who speak the same language no longer understand one another. Likewise, in a religion the diversity can be so great that the beliefs and practices of one group become incomprehensible to another. A Japanese Zen Buddhist has no idea how to perform the rituals in a Thai Theravada temple, and a Protestant Christian who is used to an extremely austere church building does not always feel at home among the many icons and statues of saints in a monastery of Orthodox Christians.

We can likewise easily accept that languages are not “invented”, “prescribed” or “imposed”, but rather “originate”, “grow”, and “change”. Even though certain reference books might determine the correct spelling, and even though the grammar rules of “standardized language” is laid down by linguists and taught by language instructors, we realize that languages are constantly evolving in people’s daily communications. The same applies to religions: even if a specific religious community recognizes holy scriptures, and even if they have some sort of priestly class, their religion still continues to evolve in the daily experience of their faith.

Finally, just like there are fundamentalists in religions who want to keep their religion as “pure” as possible, there are also language purists in every linguistic area. This “purity” is not proclaimed by priests but preached by schoolteachers and sometimes even by nationalist political leaders who base their power on perpetuating a specific cultural identity. They often look down on certain dialects and slang, thus ignoring how much these variants are an undeniable part of the actual language diversity. They will similarly sometimes pretend the correct language rules have always been the same and that their language can only be spoken in one specific way. In the light of history, of course, this is nonsense. Middle English, for example, is recognizable for contemporary English speakers, but quite difficult to read. Let alone that people still speak in the manner of eleventh-century British people. Likewise, a gathering of the apostles in the early Christian communities would be unrecognizable to Christians today. To give but a few examples: the New Testament did not exist at all (and as such the first Christians were mainly familiar with the Jewish Torah); there was no mention of a central doctrinal concept like Trinity in the first two centuries of Christianity; and important Greco-Roman philosophical concepts, which were unknown to Jesus’ disciples, had yet to be infused into Christianity by the Church Fathers.

That does not mean, of course, that everything is completely incohesive and amorphous. Certain elements do bind a religion together, but these elements are always flexible. This too is akin to language: languages undoubtedly have a distinctiveness because of the conventions concerning their vocabulary and grammar, but these conventions are always subject to change as well.

In short, one can think of religions as languages which do not consist of vocabulary and grammar, but of symbols, rituals, stories, ideas, and ways of life. From this perspective, the inherent flexibility of religion - which is all too often ignored in public discussions on religion - becomes much easier to understand, because even though these symbols, rituals, stories, ideas, and ways of life determine the distinctiveness of a tradition, they are simultaneously always subject to change.

This extract was slightly adapted from the title by the author to fit the format of an op-ed article.

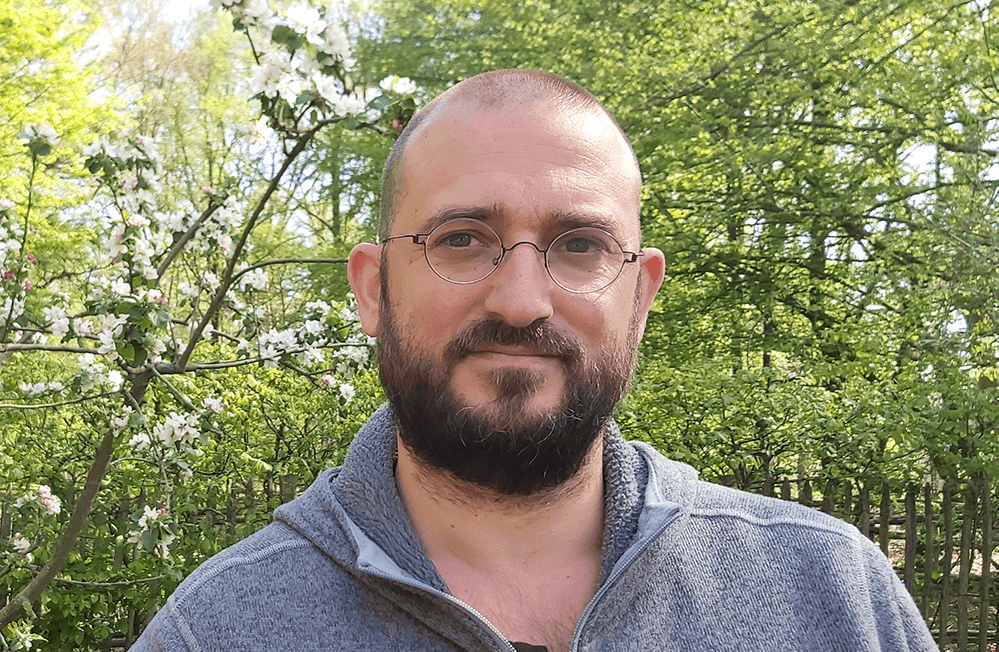

About the author

Jonas Atlas is a Belgian scholar of religion who writes and lectures on religion, politics and mysticism. Though rooted within the Christian tradition, Jonas immersed himself in various other traditions, from Hinduism to Islam. After his studies in philosophy, anthropology, and theology at different universities, he became active in various forms of local and international peace work, often with a focus on cultural and religious diversity.

Jonas currently teaches classes on ethics, spirituality, and religion at the KDG University of Applied Sciences and Arts. He is also an independent researcher at the Radboud University, as a member of the Race, Religion, and Secularism network.

His previous books include “Re-visioning Sufism”, which reveals the politics of mysticism behind the contemporary portrayal of Islamic spirituality, and “Halal Monk: a Christian on a journey through Islam”, which gathered a series of interreligious dialogues with influential scholars, artists, and activists from the Islamic world. The latter won the 2015 Belgian Religious Book of the Year audience award.

Jonas is also the host of Re-visioning Religion, a conversational podcast series on the crossroads of religion, politics and spirituality.

Jonas Atlas | Contributor

Jonas Atlas is a Belgian scholar of religion who writes and lectures on religion, politics and mysticism.

You can find him on online here: jonasatlas.net